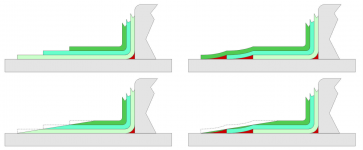

While that's probably true, who grinds/sands down the edges of their tabbing? I think there's arguments for both ways, but I just went with smallest first, as it made the most sense to me.

These were the explanations given to me below (these were all questions I had asked because I was really trying to get my head around both explanations and see where everyone was coming from because it's such a highly debated topic).

Q: when do you grind down tabbing anyways?

A: There are plenty of regions you need grind down tabbing, such as when prepping for bilge paint, epoxy to get rid of blushing, recoats of paint in the future, and others. We're talking extremely thin layers of cloth make up the tabbing, so even slight scuffings are taking material away from the overlapping tab bends where they're already having trouble (albeit small) and creating a weak point in the tabbing.

Q: But isn't it better to have more security by having more layers contact the original hull!?

A: Your mind would tell you that, but when the tabbing is overlaying itself at 90degree bends, you're creating small air pockets and resin rich areas that will be extremely brittle. Whereas with the biggest layer first, you have more square MM for square MM solid contact, while you're also avoiding resin rich lines at the end of each tab if running small to large. If you are worried about delaminations and expecting smaller subsequent sections of other layers to hold on, you're in for a bad time. If your prep work is solid and correct, delamination won't be an issue anyways. If you slip up and don't prep correctly, it doesn't matter what type of tabbing layup is on there, they'll all delaminate.

Q: But... wouldn't the forces translate better going from small to large, like, help with the attempted torsional twist or bending and popping of the stringer?

A: No. When using small to large, you're essentially cutting away the overall length of your tabbing strength, and relying on one layer at a time for each layer's end that sticks past one another because the force is wanting to pull up, not really torsional or torquing forces. The force of supporting the stringer will come from each layer above, sharing some force load from the layer below. If they're overlapped small to large, you're relying on only small strip taking the brunt of the load first, and transferring leftover energy directly above it, which the next layer is now relying only on the small section at its end trays only a couple inches longer to hang onto the hull, and so on. With larger tabs first, the length of the first layer has much larger complete and unbroken bond with the hull - because there's no weak, brittle, resin rich lines to contend with - and it transfers the upward pulling load progressively back into the bulk of the thickest part of the lamination at the base of the stringer and fillets. You also need to consider that manufacturers are moving like an assembly line and many are not hand laid jobs with the utmost of care. Some guy may be having a bad week and spray too much or too little resin. He may be careless on the application of the cloth, or may just overall trying to rush. This is another reason for large to small, because of the adhesion points I told you about earlier with more surface area being in contact with the hull. These guys are laying brand new glass on brand new hulls that haven't been battered, and tons of years of inconsistencies that may pop a tab from the hull's floor even if doing a crappy job.

Q: Well, when are each methods more preferred over one another then?

A: There's a reason that the largest prominent builders/companies use largest to smallest tabbing, and most of it is dictated by experience and countless dollars of engineering and testing. There are a lot of articles and results on this very issue in Boat Builder Magazine. But, and this is a big but, both methods are used in various situations and methods of laying glass. Remember though, these are brand new glass and materials being put onto brand new hulls that need zero prep and are virtually wet on wet or wet on tacky installs. So for stringers, it's almost exclusively largest to smallest tabbing, unless they're using a vacuum system to eliminate the resin rich lines and air pockets where subsequent larger layers overlap when going from small to big. Also, composite stringer versus wood stringer has a factor too. When using wider bulky composites, or relying solely on glass and knowing the internal stringer will not rot away or become weakened due to possible water entry, small to big is used almost exclusively in addition to the tabbing being much larger for the exact reasons you mentioned before - because the extra layers will grab as security layers, since not having to rely on solely the tabbing alone in the event the stringer rots away or is compromised by water intrusion like with wooden stringers. With the advances in tech, materials, and various resins across the board over the past decades, it's really less of a concern today as it would be in yesteryears as to which tabbing layup is used if done correctly either way. But for lumber stringers and planning for the long haul, that's why the largest company's including ours, tab from large to small. But it's really just a choice best made by the individual builder and what they feel is easier and most adequate for their build.

(---- End of questions ----)

So, what I seemed to gather from all of it, is that with today's superior resins, cloths, and manufacturing methods, it's really an apples to apples comparison. I don't think you can really go wrong in either direction when it comes to non-rushed hand laying like most of us are doing (unless building really skimpy on the verge of borderline underbuilding). So... until I'm building a lightweight racing hull for a trans-international racing company, I think I'll stick with small to large. Even if not just for the mental security since I overbuild everything anyways and I like the idea of subsequent layers grabbing the hull, lol.