JB

Honorary Moderator Emeritus

- Joined

- Mar 25, 2001

- Messages

- 45,907

From various posts on different threads, there seems to be a lot of misunderstanding when it comes to metallic corrosion and its protection on small boats, so I’ve taken the liberty of posting the comments below. If there are any experts out there who can add to this information, I’m sure it will be welcome. These comments are an over-simplification, and serve to hit the bones of the corrosion problem only, but sufficient information is here to help identify and fight most small boat corrosion problems.

Water. All water is an electrolyte. Corrosion slows in fresh, still, cold water, and is faster in warm, clear, moving salt water. That’s why a cold battery has less power to crank your car than a warm one. So fittings on a boat used in Northern lakes will last longer than in a Californian bay. This also means that corrosion can take place while your boat is on its trailer, if it has bilge water, sodden flotation foam, damp sludge in the leg, or even if it stands in the rain.

Galvanic Corrosion. This is the correct term, although we commonly call it electrolytic corrosion. In the days of sailing ships, it was found that screwing a lump of scrap iron to the copper-bottomed hull preserved the copper from corrosion. Investigative science followed from there, and today we can table a whole range of metals in order of their susceptibility to galvanic corrosion. At the top (most noble) are platinum, gold, titanium and 316L stainless. At the bottom (least noble) are metals like cadmium, zinc, and magnesium. When a galvanic couple forms, one of the metals in the couple becomes the anode and corrodes faster than it would all by itself, while the other becomes the cathode and corrodes slower than it would alone. The driving force for corrosion is a potential difference between the different materials, and water - any water - completes this circuit.

The metals that concern us are listed here, in order of their resistance to electrolytic corrosion:

LEAST ANODIC (Most Noble) hard to corrode

Titanium

Stainless steel - high chrome (i.e. grade 316L)

Nickel (passive)

Bronzes

Copper

Brasses

Lead

Stainless Steel - low chrome

Cast iron

Wrought iron

Mild Steel

2024 aluminum

Zinc Magnesium and its alloys

MOST ANODIC (least noble) easy to corrode

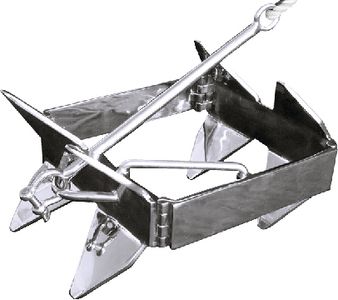

Compatibility. Metals closest to each other in this Table will have the least tendency for the ‘weakest’ to corrode. Metals farthest apart will have the greatest tendency. This is good news and bad news. Use widely dissimilar metals on your underwater fittings - aluminum and stainless, for example - and you have a large corrosion potential. Sacrificial anodes, on the other hand, are purposely made from metals that easily corrode (that's why we loosely call them 'zincs'). Correctly sizing, placing and maintaining these anodes utilizes this incompatibility to good effect.

Proximity. Bad news - the closer dissimilar metals are to each other, the greater the tendency for the least noble to corrode. This means that if you have a stainless prop on an outboard leg, the leg could corrode faster than it would if you had an aluminum prop, because aluminum is ‘weaker’ in the galvanic table. The same principle applies to the proximity of any other underwater fitments. Even stainless steels, depending on their content (low chrome or high chrome) can have widely diverse corrosion resistance, and putting two types of stainless in close proximity will speed up the corrosion of one of them. The good news is that fitting anodes either in close proximity or in physical contact with ‘weak’ metals will prolong their life. So a zinc screwed tight to your out drive leg will protect both the leg and the aluminum prop. Contact. Dissimilar metals in physical contact will accelerate the corrosion of the ‘weakest’. Screw a stainless bolt into an aluminum hull and corrosion will take place on the aluminum around the bolt head. No easy cure for this one, unless you also use zinc washers under the bolt head, but these will cause leaks as they corrode away. Best not to do it at all. That’s why aluminum boats use aluminum rivets.

Cure? There is only one complete cure - keep your boat warm and dry, and never take it anywhere near water!

Precautions. Reduce the number of dissimilar underwater metals where possible. Keep most noble and least noble fittings as far apart as possible. Fit correct anodes (differing waters require different anode materials) not just to your leg, but also to other major fittings around your boat. If anodes are not fitted to stainless swim ladders or trim tabs, these items can speed the corrosion of less noble metals elsewhere on your hull - like your expensive outboard leg! Notice that most metallic fittings are on the transom - all in proximity to each other! Keep all anodes clean, regularly remove the whitish oxide that forms on the anodes with a file if necessary, and replace them when they are half gone.

As I said - this is an over-simplification, and there are a lot of variables. But the bottom line always is - neglect spells future expensive trouble.

Ciao

Water. All water is an electrolyte. Corrosion slows in fresh, still, cold water, and is faster in warm, clear, moving salt water. That’s why a cold battery has less power to crank your car than a warm one. So fittings on a boat used in Northern lakes will last longer than in a Californian bay. This also means that corrosion can take place while your boat is on its trailer, if it has bilge water, sodden flotation foam, damp sludge in the leg, or even if it stands in the rain.

Galvanic Corrosion. This is the correct term, although we commonly call it electrolytic corrosion. In the days of sailing ships, it was found that screwing a lump of scrap iron to the copper-bottomed hull preserved the copper from corrosion. Investigative science followed from there, and today we can table a whole range of metals in order of their susceptibility to galvanic corrosion. At the top (most noble) are platinum, gold, titanium and 316L stainless. At the bottom (least noble) are metals like cadmium, zinc, and magnesium. When a galvanic couple forms, one of the metals in the couple becomes the anode and corrodes faster than it would all by itself, while the other becomes the cathode and corrodes slower than it would alone. The driving force for corrosion is a potential difference between the different materials, and water - any water - completes this circuit.

The metals that concern us are listed here, in order of their resistance to electrolytic corrosion:

LEAST ANODIC (Most Noble) hard to corrode

Titanium

Stainless steel - high chrome (i.e. grade 316L)

Nickel (passive)

Bronzes

Copper

Brasses

Lead

Stainless Steel - low chrome

Cast iron

Wrought iron

Mild Steel

2024 aluminum

Zinc Magnesium and its alloys

MOST ANODIC (least noble) easy to corrode

Compatibility. Metals closest to each other in this Table will have the least tendency for the ‘weakest’ to corrode. Metals farthest apart will have the greatest tendency. This is good news and bad news. Use widely dissimilar metals on your underwater fittings - aluminum and stainless, for example - and you have a large corrosion potential. Sacrificial anodes, on the other hand, are purposely made from metals that easily corrode (that's why we loosely call them 'zincs'). Correctly sizing, placing and maintaining these anodes utilizes this incompatibility to good effect.

Proximity. Bad news - the closer dissimilar metals are to each other, the greater the tendency for the least noble to corrode. This means that if you have a stainless prop on an outboard leg, the leg could corrode faster than it would if you had an aluminum prop, because aluminum is ‘weaker’ in the galvanic table. The same principle applies to the proximity of any other underwater fitments. Even stainless steels, depending on their content (low chrome or high chrome) can have widely diverse corrosion resistance, and putting two types of stainless in close proximity will speed up the corrosion of one of them. The good news is that fitting anodes either in close proximity or in physical contact with ‘weak’ metals will prolong their life. So a zinc screwed tight to your out drive leg will protect both the leg and the aluminum prop. Contact. Dissimilar metals in physical contact will accelerate the corrosion of the ‘weakest’. Screw a stainless bolt into an aluminum hull and corrosion will take place on the aluminum around the bolt head. No easy cure for this one, unless you also use zinc washers under the bolt head, but these will cause leaks as they corrode away. Best not to do it at all. That’s why aluminum boats use aluminum rivets.

Cure? There is only one complete cure - keep your boat warm and dry, and never take it anywhere near water!

Precautions. Reduce the number of dissimilar underwater metals where possible. Keep most noble and least noble fittings as far apart as possible. Fit correct anodes (differing waters require different anode materials) not just to your leg, but also to other major fittings around your boat. If anodes are not fitted to stainless swim ladders or trim tabs, these items can speed the corrosion of less noble metals elsewhere on your hull - like your expensive outboard leg! Notice that most metallic fittings are on the transom - all in proximity to each other! Keep all anodes clean, regularly remove the whitish oxide that forms on the anodes with a file if necessary, and replace them when they are half gone.

As I said - this is an over-simplification, and there are a lot of variables. But the bottom line always is - neglect spells future expensive trouble.

Ciao

Last edited: